Progress & Success, Fear & Otherization: Youn Yuh-Jung’s Oscar win amidst daily incidents of Anti-Asian Racism

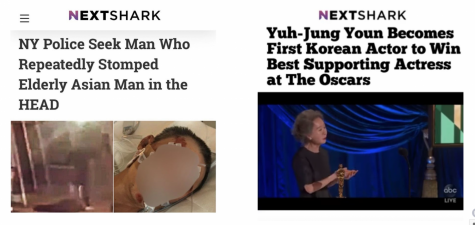

One of the most striking representations of the Asian American experience might be embodied through these two headlines, published hours apart from each other:

The report of a brutal attack on 61-year-old Yao Pan Ma came first, on Sunday afternoon, followed by Youn Yuh-Jung’s heartwarming and historic Oscar win that evening… though the order is hardly of any importance given the ceaseless cycle of hate and “acceptance” the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) community has faced for centuries.

Watching Yuh-Jung’s acceptance speech filled me with a feeling of pride and excitement similar to what I felt witnessing Parasite’s success at the 2020 Oscars. Throughout her witty address, her confidence is unmistakable, but her humility shines through above all. After thanking her Minari “family,” “forgiving” the many mispronunciations of her name, and inserting a few meta remarks about the ceremonious nature of giving an Oscar-acceptance speech, she ultimately arrives at an honest and heartening thought: each of the five nominees is a winner for their own film—unique films and roles that cannot be compared to each other in a competitive setting. Again, interjecting with a little modesty, she says that she is on stage because of a little extra “luck.”

But heartwarming, unifying moments like these—where a South Korean actress can stand on the stage of the Academy Awards with an Oscar in her hand—are tailgated by hatred, ignorance, and racism.

Striking dualities like the headlines above are a reminder:

Amidst mainstream progress towards anti-racism and the amplification of historically-repressed BIPOC voices (as performative as much of it is), there are pockets of society that try to cling to their racist roots and beliefs.

Pockets might be a misleading word here. It seems to be more like a fog of racism, with some areas denser and more occluded than others. It reaches every corner of society, from the “wokest” individuals to those who were spoon-fed racist ideologies from childhood. In areas where the fog is less dense, racism might manifest as microaggressions or the subconscious acceptance of stereotypes. And in areas where the fog sits dense and heavy, racism might manifest as untethered, unmasked hatred.

At a time when anti-Asian sentiments refuse to die down and violence born from xenophobic “otherization” has become a daily occurrence, it likely feels hopeless to even begin approaching the issue. And to a degree, I’m in agreement. It’d be a waste of energy and effort to try clearing all the fog at once by swatting it with our mere hands.

But I say to a degree, because I don’t believe it’s “hopeless.” Most of us share a vision of the day when we can break the assumption that people of color, especially those in the AAPI community, are inherently “foreign” and un-American—when we don’t see “the FIRST…” preceding awards like Oscars, or even simply when we don’t see 61-year-old Asian men collecting cans on the sidewalk being kicked to unconsciousness.

I don’t doubt that white supremacy will continue for generations in the future. But my hope is that we slowly, gradually normalize embracing the diversity of our country without the labels, at least until more and more people who believe otherwise are forced to stay quiet about their hate-fueled ideals. While rigorous demands and vigorous strides towards anti-racism are essential, it seems to hit a wall before reaching those who need to hear it most.

This is where our “mere” hands come in. The little things—our words in a conversation, the thoughts that slip through our heads, the constantly-running vigilance we keep on others and ourselves—matter so much because these are what build the environment. This might mean pointing out problematic remarks from friends and listening to better understand where we make our own. It might mean more openly expressing solidarity with other marginalized groups and becoming more involved with these issues. It’s admittedly a shallow and nearsighted resolution, since it leaves the roots of this racism untouched. But if we can create an environment that stops enabling unapologetically overt displays of hate, eliminating the normalization of hateful racism, it might just be enough to make a xenophobic attacker think twice before taking their next victim, at least.

(she/her/hers)

Anna Ryu is the Editor-in-Chief of The Shaker Bison. As a senior, this is her fourth year participating in Shaker’s school newspaper....