The Fox Eye Trend is Offensive and Racially Insensitive

The past few months have seen a surge in awareness regarding the disturbingly direct roles racism and privilege play in all of our lives. Many of us have grappled with how differently these two ever-present elements of modern society impact each and every person—we know not everyone experiences them the same. While the conversations primarily stem from and focus on anti-Black racism in particular, very rightfully so, they are also meaningful launching pads for examinations into the numerous other levels and dimensions of racism that can infiltrate our lives—and the various groups of people that can get hurt.

One group of people in the U.S. that has started to gain greater awareness through these conversations? Asians. Stifled and kept complacent for too long by the “Model Minority Myth,” the general Asian population has largely dissociated from controversial matters of “politics” and “social issues.” A long-standing expectation for indifference in these matters has permeated Asian communities, and as a result, quiet tolerance defines the history of our presence in the country. But with the gradual awakening and expanding consciousness that has ensued from late May, Asian voices are being heard—louder, stronger, with greater determination.

An issue that has raised red flags for many is the “Fox Eye” trend. Given, this is a divisive topic even amongst the Asian community. But still, the “Fox Eye” trend stands as a racially insensitive practice—one that is understandably difficult to see at first. So let’s sort through this, together.

The Problem

The “Fox Eye Challenge” is a social media trend that’s essentially made up of two parts: a cosmetic aspect, involving makeup or other facial alterations, and a physical pose. Ultimately, the goal is to achieve a “fox eye” look—elongated, slanted, and almond-shaped. Cosmetically, individuals can use eyeliner, shave and redraw eyebrows, and use thread lifts to shape and pull their eyes into the desired shape. In most cases, the eyes are physically pulled from the corners or from the temples by the hands.

It has been popularized by numerous public figures, especially in the beauty world. Famous women such as Bella Hadid and Megan Fox, and even social media influencers such as YouTuber Emma Chamberlin or Tik Tok user Melody Nafari have shared content of themselves doing the “challenge.” For a sizable number of people, this looks like any other beauty fad or modeling pose. But for a strong majority of Asians (particularly Asians in the U.S.), this is an offensive and ignorant gesture that belittles generations of racism against our community.

I think many of us can identify what racism against Asians looked like for our generation growing up. Perhaps you can bring to mind the subject for one of the longest-standing, most infamous torments—Asian eyes. “Squinty.” “Tiny.” “Slits.”

It is a familiar gesture for communities across the country. The hands come up to the sides of the face, and the corners of the eyes are pulled.

What pains me about this gibe in particular is that I was often on the dispensing end. To my younger self, it genuinely seemed like a harmless joke. Nothing seemed wrong about joking about our eyes, Asian eyes, especially when it was a stereotype that seemed as common as any normal conversation. Little did I know the harmful idea it perpetuated, that Asian eyes were something that should be pointed out and emphasized. Because you could say that there’s technically nothing objectively wrong with observing that they’re “small.” But if you stop looking through that unrealistic, “objective” lens, it becomes clear how wrong it really is—the highlighting (and sometimes blatant mocking) of these differences is what drills into Asian minds: “I am different. I am not what they are.”

When countless Asians grow up hearing this—whether it’s one time, or three times, or every day, or indirectly through other Asian friends, or even tangentially through the widespread stereotype itself—we grow up to be in a constant state of awareness. A sharp awareness of what makes us not normal, not belong, and always a little uncomfortable—as if we’re a guest visiting someone else’s house.

The recent “Fox Eye” trend presents a mutation of this original issue. As non-Asian public figures use cosmetics and poses to artificially create the eye shape that countless Asians are born with, they benefit by gaining praise and popularity… for the same look that generations of Asians have been mocked, degraded, and hurt for.

Claire Kim, a Korean American student at Shaker, recounts her own difficult journey to accept and appreciate herself—her eyes, in particular. She finds the trend incredibly insensitive.

“In a way it invalidates the struggle Asians have had with accepting their appearances,” she writes.

We are shown that our eyes can be taken in and out of “fashion” and “popularity” as a trend, when white (and non-Asian) people find it convenient for their “aesthetic.”

It is ignorant and upsetting.

So What? Stop Being So Sensitive.

This is where I’ll be absolutely candid. Because I get it, if you don’t quite see the problem yet, or question how big of a deal this actually is. Like I mentioned earlier, I’ve been relatively lucky in all of this. As an Asian-American growing up in New York, I’ve lived in a pretty sheltered bubble—not just in the school districts and communities, but in the friends I’ve been lucky enough to find.

I don’t recall ever being associated with “squinty eyes,” much less mocked or bullied for it. Yet, I was very well aware of the stereotype’s existence, making my own jokes and pointing out the eyes of my fellow Asian friends. As mild as it might’ve been, I fed the racism. I thought, “If I, an Asian, don’t find it hurtful… it must be that way for everyone else.” All I knew was that it didn’t personally bother me, as an Asian-American, and so I instead grew to question it when it did bother my other Asian peers.

That’s the sad danger that comes with this issue. It is too often overlooked as trivial and insignificant; anyone who takes offense to it is “exaggerating” and being “sensitive” over “just some makeup” or “just a pose.” But here’s what I had to realize, here’s what all of my fellow Asians have to realize, and really, here’s what we all have to realize.

You do not get to define what is offensive to another person.

My Asian peers—recognize we are not a monolith. If you don’t understand why anyone would find this offensive, if you find yourself shrugging off the “Fox Eye” trend, if you find yourself belittling the stories of other Asian individuals who are hurt, please recognize that each of our personal experiences cannot represent and invalidate the experiences of another.

And to everyone—I say again, none of us can determine what others find offensive or hurtful. Your intentions do not decide how it affects others. Even if you or I “didn’t mean it to be offensive,” that won’t change how another person receives and interprets it.

It is ignorant and upsetting, no matter how unintentional.

The Bigger Picture

“Chinese, Japanese, Dirty Knees, Look at these!”

Our discussion might seem a bit zoomed in. So let’s step back and view the bigger picture, for a moment.

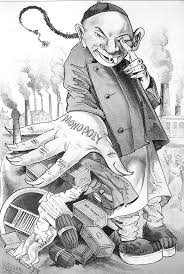

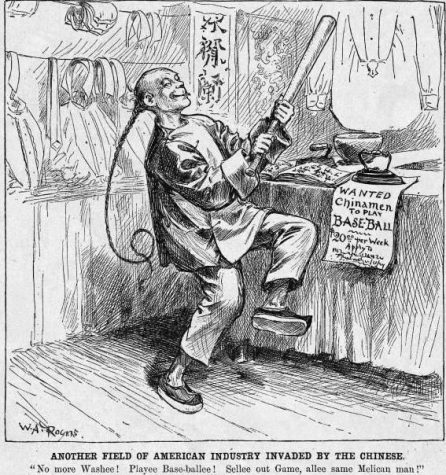

From the first time Asian individuals set foot in the United States, they were ostracized and rejected by the determinant of the “normal” or the “standard”—white society. Those who arrived during the first major wave of Asian immigration in the late 19th century were subjected to ruthless, undisguised racism. Early portrayals of Asians in the U.S. were racist depictions meant to aggressively exaggerate the ways Asians were “different,” “foreign,” and not like the “normal,” “standard” U.S. citizen (A.K.A. not white)—be it the eyes, the hair, the teeth, the hats, the clothes. These dehumanizing stereotypes were a way for those with power in the social and racial hierarchy of the U.S. to push down anyone who didn’t meet the criteria to be on their“level” (A.K.A. anyone who wasn’t white).

I’m sure we’re all well aware of this country’s disturbing history of covert racism and xenophobia to some degree. And how, as we’ve become more diverse and aware and considerate, millimeter by millimeter, generation after generation,

many of the blatant offenses have been subdued. (I mean, not even 100 years ago, this country’s “highest court of the land” was rejecting Asian immigrants for citizenship on the basis of not being “white” enough… [see Ozawa v. United States and Thind v. United States] We’ve certainly progressed from there, at least.)

But I hope that we’re also aware that it has only learned to conceal itself in subtler ways over time. I hope we’re aware that the othering of Asians in the U.S. has not disappeared by any means.

It can look like strangers screaming, “Go back to your country!” on the street. It can look like co-workers commenting on “how good your English is, for someone like you!” It can even look like students disdainfully pinching their noses while peering at your food during lunch.

Chinese-American senior Yifan Kao recalls the passive-aggressive judgments and questions she’s faced regarding her food—particularly throughout younger grade levels. The stares and occasional “What is that?” made her feel embarrassed, insecure, and ashamed to be Asian, she says.

“Being one of the only Asians at school at the time (Kindergarten–3rd grade)… it only made me stand out more when people pointed it out… it only added on to how different I was.”

She remembers eventually caving and starting to buy school lunches “to avoid all of it.”

This brings us back to our “Fox Eye” trend. Covertly letting Asians know: the same features we degraded you for are now what we’ve claimed as “in style.” The same gestures we used to make you feel abnormal are now what we use to make ourselves feel “beautiful.”

There’s a disturbing, unspoken power dynamic there that allows many Asian voices to be drowned and many Asian experiences to be ignored.

What can you do?

Luckily, remedies to this particular issue (not necessarily the entire institution of racism, unfortunately) are simple.

For one, non-Asian individuals can stop participating in the “Fox Eye” trend. Beauty can be created in looks that don’t insensitively trample over the countless years of pain, through more deliberate care and awareness.

More importantly, we can all listen when people express their pain. Instead of trivializing and putting them down, dismissing them to be “too sensitive” or “overreacting,” we can open ourselves up to broadening the relatively narrow scope of understanding that our single own lives may give us.

And lastly, there can be incredible strength in acknowledging, accepting, understanding, and learning from past shortcomings. We know intentions can’t determine how others are impacted, but nothing is unforgivable—as long as we are constantly trying to grow towards improvement and greater consideration for others.

It is true that we’re looking at a small thread of the cloth that is the true problem. But that doesn’t mean small adjustments and tweaks in awareness aren’t worth pursuing.

If the solution can be as simple as not doing it, why not? If a number of individuals from a community have voiced their discomfort, why don’t we listen?

(she/her/hers)

Anna Ryu is the Editor-in-Chief of The Shaker Bison. As a senior, this is her fourth year participating in Shaker’s school newspaper....