April 4, 2025, will mark 57 years since Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. King proclaimed his vision of racial equality and justice, a nation living up to its ideals, a “beloved community” rooted in unity, and of transforming seeds of discord into a symphony of brotherhood.

I was in fifth grade when I attended Dr. Paul Murray’s Music of the Civil Rights Movement class with my mom. The class was resounding with songs from the Civil Rights Movement– “Oh Freedom,” “We Shall Overcome,” and “A Change is Going to Come.” Holding hands, the audience sang and tapped their feet to the songs that inspired, mobilized, and gave voice to the movement that revolutionized America. In February 2024, I saw Dr. Murray’s Journey to Freedom Project. The Journey to Freedom Project presents oral history interviews of social justice advocates and civil rights activists from the Capital Region: Patricia Barbanell, Susan Butler, Andressa Coleman, Miki Conn, Judith Fetterley. Jeanette Gottlieb, Stephen Gottlieb, Alice Green, Julie Kabat, Bill Leue, Jim Owens, Anne Pope, Dorothy Singletary, Nell Stokes, and Dr. Paul Murray. Journey to Freedom | Siena College

I was thrilled when Dr. Murray agreed to speak with me about the Journey to Freedom Project. Dr. Murray is a retired Professor of Sociology who, for more than 37 years, brought the Civil Rights Movement to life in his Siena College classrooms. After his retirement, he forged the Journey to Freedom Project, a twelve-part video series highlighting the efforts of civil rights leaders and “foot soldiers” in pioneering change. In our 90-minute conversation, Dr. Murray shared valuable insights, from his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s to the Journey to Freedom Project.

1. Before talking about the Journey to Freedom Project, can you share a bit about your personal background and how you became involved in the Civil Rights Movement?

I attended a Catholic high school in an all White suburb in Detroit. I was invited to attend an assembly for high school students sponsored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews and the theme was brotherhood. The guest speaker was on the Supreme Court of the state of Michigan, and he talked about national developments in the field of civil rights. This was 1961, and he made frequent reference to the desegregation of Little Rock high school in Arkansas. In addition, when we broke up into smaller discussion groups, I met a Black college student from the University of Detroit named Charles, and he quickly took an interest in me. He was a rather sophisticated individual who had a lot of knowledge about civil rights. I ended up enrolling at the University of Detroit and Charles was there and I joined the human relations club and before long I was doing what he had done— visiting local high schools and giving talks about civil rights. During the 1960s there was a lot going on in the south. The summer of 1964 in particular was extremely important in my life. That was called freedom summer, where college students from the north were recruited to go to Mississippi and work for voter registration. I helped to address a weekly newspaper that informed people about what was going on in the Civil Rights Movement that was put out by the student nonviolent coordinating committee. I graduated and before I began working on my master’s degree, I had the opportunity to volunteer for a project that was organized by the American Friends Service committee who work for social change through various volunteer projects. I was also a volunteer for the Head Start project where I was an assistant in a classroom. I spent most of the summer working with these young kids— singing songs, teaching them games, beginning to work with colors and alphabet, etc. And these kids came from such a poor community and I had never seen poverty at that level. The main way poverty manifested itself was in the lack of health care.

(Shows the University of Detroit Human Relations Club which Dr. Murray joined under the guidance of Charles Cotman)

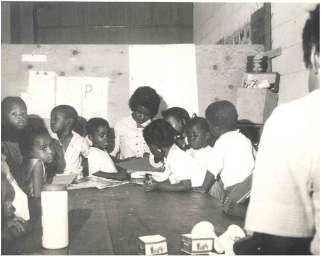

(Head Start class where Dr. Murray volunteered as an assistant in the classroom)

I enrolled at Ohio State University to get my masters degree. I wrote my master’s thesis on a community in Mississippi where I volunteered for a while, and then went to Florida State University where I got my PhD degree. So after I completed my PhD, my first teaching job was at a small college in Jackson, Mississippi, and from time to time I went back to Madison County. I got involved with civil rights groups there in Jackson and one of the things I was able to do was to use my statistical training to analyze voting statistics. This was needed because there were lawsuits going on challenging the electoral procedure. There’s a situation where, for example, if there were five people who were representing a city in the state legislature, instead of being elected from specific neighborhoods in a city, they were elected on a large basis. So if you had a city like Jackson, Mississippi, where we lived, now it’s majority Black, but at that time the majority of the registered voters were White. And so they could elect an all White legislative delegation, even though 40% of the population of the city were African-American. The same thing was happening in many other districts, and I was able to do statistical analysis that was required in order to prove, in fact, that this was going on, that it had a detrimental effect on Black representation and ultimately several of the cases were decided on a favorable basis. Eventually, I left college and spent a year in Birmingham, Alabama. Then I got hired at Siena and embarked on my Siena career that lasted nearly 40 years and the courses I most enjoyed teaching were Race Relations and Collective Behavior and then I created my own course on the Civil Rights Movement, which was a great deal of fun. On two occasions I had the opportunity to lead groups of students to the South– one with Siena students, another with Albany high students.

2. In your interview for the Journey to Freedom Project you mentioned that you marched with Martin Luther King Jr: What was that experience like?

At the end of my freshman year in college, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Detroit. There was a large march called the walk to freedom and this was a week or two weeks after the end of the demonstrations in Birmingham. It was a major victory for Martin Luther King Jr. and his movement. I was with a group of my friends from college and we were a very small part of the 125,000 people who marched down the main street in Detroit. It was pretty awesome. Dr. King gave an address at the conclusion of the march. The seats were already taken inside the auditorium, but they piped out the speech on speakers to everybody who was standing outside. A few months later, a mother of a friend of mine called and said, Paul, we’re sending a train to the March on Washington. You know, would you like to be a part of it? And I was working my summer job and the march was in the middle of the week and I would have had to take off two or three days from work and I didn’t feel like I could sacrifice the income. And besides, I’d already heard Martin Luther King Jr. I said, been there, done that. And of course nobody remembers the march in Detroit and everybody remembers the March on Washington. But it was a marvelous, marvelous event and, you know, something that I’m very, very pleased that I was able to be a part of.

During my time in Mississippi, it was the time of a civil rights march, not as well known as the Selma Montgomery march, but it was called the March Against Fear. It was designed to encourage people to take advantage of the Voting Rights Act. The marchers had come in the previous night and they had been tear gassed by the state police. Martin Luther King Jr. was leading this march and one evening he had been in a meeting and we were assembling for a march. He was not going to be marching, but he passed by in a large black sedan. He was being driven to the home where he was staying and I was standing from here to there, from Martin Luther King Jr., only he was inside the limo going out and I was outside, looking in. So that was the second time. I was in much closer proximity on that occasion than when in the Detroit March where I never saw Dr. King. He was just surrounded by so many other people.

(Shows Dr. Murray and some college friends at the 1963 Walk to Freedom Detroit march led by MLK Jr.)

I remember the evening when the news came that Dr. King had been shot. And I was meeting with a fellow graduate student and he was a Catholic priest and so he was staying at the Catholic church that was associated with the Florida state campus. And I remember one of the other priests came into the room where we were and he said, you know, Dr. King has been shot, they are going to run amok and I knew that he was referring, of course, to the Black people who lived in Tallahassee. There was a Black community, a very poor Black immunity, not far from the university campus. But the idea that this priest is not going to mourn the passing of Martin Luther King Jr., but is going to worry about his church, maybe the subject of some kind of an attack by rioters was just terribly distressing to me, to say the least. There was a memorial service on the campus. I was invited to be one of the speakers and I recently discovered the text of the talk that I delivered on that occasion. But it was a very distressing period to say the least.

3. Moving to the Journey to Freedom project itself: How did you conceive the Journey to Freedom Project?

It evolves from my course on the Civil Rights Movement. I taught it every other year over a period of probably 20 years or so. I began to realize that students might get tired of listening to the same voice class after class and so I started looking for speakers to invite to the class. I remember Bernice Johnson Reagon, who was a speaker one year. She was a member of the freedom singers as a student, and she toured the country singing freedom songs and raising money for the student nonviolent, coordinating committee. Later on she became the leader of an acapella local group called Sweet Honey in the Rock that performed nationally. She came to my class and talked about the importance of the music of the civil rights movement and led the students in singing a couple of songs. The very last class, before I retired, I had students film the class and we made a video, and that kind of inspired me wishing that we had videos of the guest speakers who came to my class. I mulled that over for a couple of years and then one of the people, one of the most wonderful speakers passed away. Al Gordon had been a freedom Rider in 1961. He was a teacher in a New York city school. He went south on the bus and he was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi. He spent 30 days in a penitentiary. He went back to Mississippi a couple of years later to work on voter registration. What made his story more compelling was that as a young boy, he arrived in the United States to escape the Nazi persecution. He became a citizen and was very active in working for social justice. He was just a wonderful person. His death motivated me to go ahead and begin to start this project to film the other people who had been speakers to my class. I had to raise some money to hire some videographers. I had a list of people that we wanted to interview. All of them agreed to be interviewed. We wound up with a total of 15 individuals who were filmed two summers ago. Then we spent a few months editing the videos, putting everything together. Since that time, Alice Green, who was one of the key people that we filmed, has passed away, but fortunately, we have her story on video for students like yourself and your classmates to listen to and to be inspired by. We’ve got videos of people who’ve had a variety of different experiences. My friend Jim Owens was attending a Catholic elementary school in Wilmington, Delaware. Now, at that time I wasn’t aware that Delaware was a Jim Crow state. I always thought of it as being part of the north, but it was really kind of a southern state right on the Mason Dixon line. And the schools in Delaware were segregated. There was no Catholic high school or actually there was no Black Catholic high school in Wilmington. Jim was a very, very devout Catholic boy who spent a couple of years in the seminary and he didn’t want to go to the public school. A well-to do Black woman paid his train fare so he could commute to Philadelphia which is about 30 miles or so from Wilmington. He’d get up in the morning, take the train to Philadelphia, and do his homework on the train back home. He did that for his freshman year and beginning of his sophomore year ,when his parents were approached by the principal of one of the Catholic schools saying, “I hear your son is going to Philadelphia to get a Catholic education. He shouldn’t be doing this.” That Catholic school had been all white up to that time. The principal of the school had tried to enroll Black students three years earlier, but his religious superiors said no. But after a while, he got support from some very influential Catholic people in the community, a judge, a woman who was a part of a very wealthy, well connected family. Without any advance notice, without any fanfare, in November in the middle of the school year, five young Black men enrolled in that school, and they became the first Black students to attend integrated schools. Jim now lives in Albany. I met him when he was a student of mine and when we were on break he started talking about being one of the first Black students at his school. I followed up on that and he and I went to Wilmington and interviewed some of his classmates and other people. That became an article that we submitted to the history journal in Delaware. That marked the beginning of me writing a larger number of articles about the Civil Rights Movement.

Probably the most remarkable person, aside from Alice Green, was Julie Kabat. Julie was not a civil rights volunteer. She had an older brother who volunteered for the freedom summer in 1964 and went to Philadelphia, Mississippi, which was where Goodman Schorner and Cheney had been working. Her brother taught in a freedom school there. He was in medical school at the time and so he taught the kids in the freedom school basic biology, things that they didn’t get in their segregated public schools. And unfortunately, he passed away only a couple of years after finishing medical school. I met Julie when I took a group of students down to Mississippi and this was the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer and I met her on the campus of Tubaloo College, and we discovered, of course, we were both from the Albany area. That was quite a coincidence, and then she started talking about her brother and I invited her to come to speak to my students and she brought Dorothy and Andrea, two women she met when she went back to Meridian, Mississippi. They were students in the freedom school that her brother had taught. It was just so moving to listen to the two women talk about the experience of these White civil rights warriors coming into a town like Meridian, Mississippi.

So, anyhow, we got 15 of these volunteers on film and then, of course, we did the editing and now it’s all available on the Internet all available on YouTube and part of your homework assignment you have to go and watch all 15.

4. The Civil Rights movement gave home to so many different voices from different backgrounds, and that was evident throughout the Journey to Freedom Project. Can you talk a bit about the Civil Rights activists you chose to be a part of this project?

All of them had been guest speakers in my class, so that was easy. Most of them were available in the immediate area, so that wasn’t too difficult. How I went about discovering them to invite them to come to my class was more complicated. I guess I just kept my ears open and I was active in circles that were involved in working for civil rights. I encountered Alice Green on many different occasions, and the same thing with Anne Pope, who was head of the NAACP for many years. Nell Stokes, who helped at the Montgomery Bus Boycott, arrived in Albany on a Greyhound bus with three children, where she began to experience a different kind of racism.

Mickey Conn, Mickey’s father was a physician and her mother was an artist. Mickey and her sisters were the first Black students, the only Black students at Bethlehem high school for many years. Mickey then decided to go to Howard University where she was involved with a very active civil rights organization and her interview segment talks about working to prepare for the March on Washington. She offers a very poignant description of the early morning hours when she was there before the crowds arrived and she was setting up the booth that she was operating and it was kind of misty and you really couldn’t see and nobody knew exactly how many people were going to show up. And gradually the people started coming and the fog lifted and of course, it was a remarkable day.

Jeanette Gottlieb’s story is very interesting. She grew up in rural North Carolina, kind of a mountain community and she was the first person in her family to go to college. She enrolled in North Carolina College for Women, which was in Greensboro, North Carolina. Greensboro, North Carolina is famous in the history of the Civil Rights Movement for being the scene of the initial sit-in demonstration by Black students at North Carolina A and T. Anyhow, she got together with a couple of her friends and they had a few Black women living in her dormitory. Four of the students, two Black and two White, went to the local movie theater, which was operated on a segregated basis. They went up to the ticket window and said “we’d like four tickets” and the young man, probably the same age as as they were, was looking at them and saying, “I’m sorry, you know, if I sell those people tickets, they’re going to have to sit upstairs and and you’re going to have to sit downstairs” and they kept saying, “Why is that? Why do you have that policy? Well, then we’ll sit down there or we’ll sit up there.” Finally the kid got so frustrated he said, “ah, go ahead” and he sold the tickets and they broke the color barrier at the local theater there. You know, it’s not in the history books. It never got on TV, but it was four young women, two Black women and two White women that took a step for civil rights and that was happening all across the country.

Anyhow, you know, with the exception of Alice Pope and Alice Green, these people were not the leaders of the movement. These were the foot soldiers. These are the people who made the leaders, leaders. You can’t be a leader unless you have people following you, unless you have people working together with you. The message that I like to try to convey with this collection of interviews is that the Civil Rights Movement was an endeavor that involved many, many thousands of people. Not just the columns of marchers that you might see in a film on the March on Washington or the march from Selma to Montgomery. Sometimes they were the people who didn’t get any credit at all, people who were working behind the scenes, people who were involved in a movement for a short period of time, perhaps months rather than years, but they made a contribution. They came from the north and the south, and they were White and they were Black and they were Protestant and Catholic and Jewish, and there was a united undertaking. I’m afraid too often the kids in elementary school and even in high school get a picture of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, maybe Fannie Lou Hammer, and don’t appreciate very much that this was a very integrated movement. The Whites as well as Blacks were active participants. Not all of us were orators or a Baptist minister, but people who came from all walks of life and people who made their contributions in various ways.

5. How do you think today’s students understand and engage with the Civil Rights Movement?

The analogy I use is when I was a young boy growing up in the 1950s and people talked about World War I, which had ended in 1918. That was about 40 years prior to my time, and that just seemed like impossibly far back in the dim recesses of history. And I compare that to young kids today being taught about events that happened 60 and 70 years ago. You know, that’s a much further gap and it’s got to feel very, very distant from their own experience. Maybe once a year they hear about Martin Luther King and “I have a dream,” but I don’t know how much more the curriculum allows. I’m sure there is more than just that, but teachers have to rush to finish the semester and if your teacher gets too wrapped up talking about World War I, there’s not much time left over to talk about the Civil Rights movement. It’s kind of like looking at leaders like Martin Luther King for a kid today would be like looking at Abraham Lincoln in my day.

(Shows Dr. Murray and fellow work campers singing at a Black Church when they returned to Mississippi 40 years after their summer experience)

6. If you could give one piece of advice to high school and college students today, what would it be?

Don’t be afraid to get involved. There are many different ways to get involved. It doesn’t mean going out on the streets and demonstrating– it might consist of writing letters to your representatives in Congress. Each year at the Martin Luther King lecture, we give awards to three high school students. We call them the courage awards. We learn about these students from nominations of their teachers or their guidance counselors. These are kids your age who are doing wonderful things. You know, there are so many different ways to get involved and can lead to meeting different people. Take my word for it. I don’t think you’ll regret getting outside of your own little social world and exposing yourself to the diversity of people and experiences that are available to you. If you find something that you feel really passionate about, then that activism comes easily. There are many opportunities for you, but sometimes we get so caught up in our own little world. Sometimes we’re a little hesitant, we’re a little afraid of getting out there and meeting new people. I can understand that– not everybody is naturally gregarious, but again, you won’t regret it if you really make the effort to get outside of your comfortable little world and begin to encounter people whose lives are different from your own. ___________________________________________________________________________

I am grateful to Dr. Paul Murray, for his time and advice. The Journey to Freedom Project preserves the legacies of civil rights trailblazers. It is an ode to their struggles, resilience, and hope for a tolerant, peaceful world.