From Space Giants to Computers: AI Used to Improve the 2019 Black Hole Image

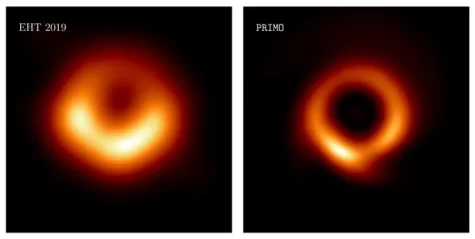

In 2019, researchers shocked the world with the first-ever image of a black hole. The terrifying behemoth, M87, had a mass 6.5 billion times that of our sun. This original image of this monstrosity is shown in the left of the two images, characterized by its menacing orange glow.

Black holes, like this one, are known for their immense gravitational strength; their pull is so influential that not even light can escape. Yet, there are still ways for us to detect these behemoths. Black holes actively feeding on matter generate an accretion disk — a ring of material that orbits it. As the matter swirls around the giant, friction heats it up, producing a soft glow. Using the Event Horizon Telescope, a set of eight radio telescopes scattered across the globe, researchers were able to detect this faint light and generate the first-ever image of a black hole. As impressive as this feat was, the photograph came out fuzzy due to the missing pieces of data the telescope array could not fill. However, now, researchers are turning to AI to combat this.

Using a new technique known as principal-component interferometric modeling (PRIMO), astrophysicists were able to sharpen the 2019 image into what you see on the right — a much more distinguishable and chilling monster. The process involved simulating over 30,000 accretion disks to find a shared pattern between them. From there, the data was used to fill in the missing pieces from the 2019 photo and generate a clearer image.

With its initial success, PRIMO has physicists all over the world excited about its implications. For one thing, the AI technology can be applied to other black holes as well, allowing for a fuller picture of these space giants. Additionally, PRIMO can help make up for the limitations of humanity. “It provides a way to compensate for the missing information about the object being observed,” said Tod Lauer, an astronomer at the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory. The improved image could also allow physicists to make a more accurate estimate of M87’s mass, enabling a better quantitative analysis alongside the qualitative.

Perhaps the most exciting thing about this technology is that it’s in its primitive stages. According to the lead author of this study, Lia Medeiros, “The 2019 image was just the beginning,” and “PRIMO will continue to be a critical tool” in unveiling the knowledge the photo holds within.

(he/him/his)

Roshan Mehta is a senior at Shaker High School, and this is his third year participating in the Bison. In the club, he serves as a writer...