We aren’t alone: What an immigrant’s story can show us about isolation

Peeling back the paper lid from its flimsy styrofoam bowl, Chang carefully removed the packets of seasoning and prepared his cup ramen. It was the evening of November 25, 1993—Thanksgiving night for most families, but just another night of studying for the international grad student. Just barely aware that such a holiday existed, he was taken by surprise when all of the local businesses and restaurants near his dorm in Minnesota shut down for the cold November day, resorting to a quiet evening in with his cup ramen, kimchi, and textbooks.

It wasn’t an unfamiliar sight for him. Ever since he’d left Korea three months ago, his experiences adjusting to the bustling new country without a car or acquaintances had built his tolerance towards the isolation that came with being a “first-year” immigrant.

This is the image my dad begins to paint as he collects our plates after dinner. Reflecting on his years as a solitary young student brings back memories that feel unfamiliar, in the company of his current family, yet unforgettable at the same time.

“I was alone. I wasn’t able to go anywhere because everyone was closed. I didn’t know too many people, because I’d just gotten here only 3 months ago. All you need is a few friends who can hang out… I didn’t even have that yet.”

He also describes the massive blow dealt by the absence of a personal car in the country. Traveling around and meeting others was difficult on their own, as a stranger to the unfamiliar neighborhood, but exponentially harder without an easy option to even try.

Settling in his chair, he chuckles as he then describes the academic pressures he felt at the time, as a student pursuing a PhD in chemical engineering.

“I had pressure to finish my homework—especially this one take-home exam, that was due Monday after Thanksgiving… my professor was very notorious for his very difficult tests.”

His school-related stresses eclipsed any homesickness and loneliness (for the most part), and in this way, he filled the emotional and social hole that’d formed after leaving home with work and responsibilities. Still, he quietly recalls words that defined that first year: “Isolated. No family.”

In the following month, Chang spent his first Christmas and New Year’s in the new country. His $14,000 annual pay as a grad student was just enough to sustain his independent living—buying a plane ticket home for the holidays was a luxury he couldn’t afford.

Being one of the students who didn’t go home for the long break, he was placed in a temporary dorm along with a sizable number of students who were staying on campus as well.

The University of Minnesota had shut down all the other dorms and most campus buildings for the holiday season, saving resources by grouping these students together. Navigating his way through the unfamiliar dorm building, he found comfort in a new group of friends—international graduate students who stayed in the country, away from family and friends back home.

Together, they discovered the optimal way to order pizza with minimal comfort speaking English: “We’ll take three pizzas with… everything.”

Each person would then pick off the unwanted toppings, forming their perfect slice.

Chang cherished the moments like this. Moments where he felt a semblance of community, connection, and togetherness.

“I only called back home once or twice a month,” my dad remembers. In the midst of recalling his memories, he describes how the technology at the time made it much harder to find these moments of connection with others. “An international call like that, through the landline, would cost 15 to 20 cents per minute so I didn’t really find myself contacting my family back home as often.”

From the other side of the kitchen table, my mom interjects with her own time as a student and immigrant in the U.S. “For me,” she begins, sitting up in her chair, “calling back home was a big part of my experience… I’d call my parents at least twice a month if I could, my sister more than that.”

She remembers saving her money and comparing call prices between phone companies to plan long calls back home. The isolation was harder for her—there would be lonely nights passed, homesick tears shed, and an aching longing to be back with friends and familiar faces.

As my parents settle together on the couch to watch the Korean news, I try to visualize their memories. Thinking about how deeply their community ties spread now, it’s almost difficult to imagine them leading such quiet, disconnected lives.

But the image of their story also comes into a clearer view. I begin to gain a better understanding of how they managed to emerge from this state of isolation and the important role their relationship played.

By 1995, they’d met and settled together in the United States, both studying for their graduate degrees. Though they found themselves married just three months after their first meeting, the solitary life they shared in the U.S. gave them a uniquely deep understanding and appreciation for each other.

Living a quiet life together in Minneapolis, their shared experience of isolation ultimately made them feel a stronger sense of togetherness.

The words “isolation” and “separation” remind me of the realities we’ve lived for the past year. While twenty-first-century technology gives us Zoom and Instagram and Discord to stay connected, it just often doesn’t feel the same. It doesn’t feel like enough.

But the stories of my parents remind me that, in our current realities, we are more together than we may feel.

The experience of an immigrant is not an uncommon one, but it is often a story of individual burden, rarely shared or even heard by others. For many immigrants, separation from loved ones and disconnection from the community are familiar storms that have been quietly weathered for generations.

The isolation we feel now is understood by the entire world. A click onto social media shows us a relatable quarantine meme, a text to a friend gives us a refreshing opportunity to rant, and the word “unprecedented” has etched itself into our collective vocabulary.

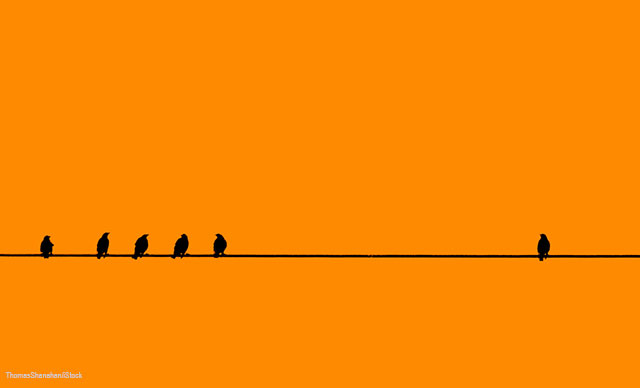

While it’s hard to feel any sort of “togetherness” at all right now, I’ve started to see the subtle force that binds and draws us all closer together—our shared experience.

In a way, our isolation connects us.

(she/her/hers)

Anna Ryu is the Editor-in-Chief of The Shaker Bison. As a senior, this is her fourth year participating in Shaker’s school newspaper....